The Smiley Face, or “happy face” symbol, is so ubiquitous in pop culture that it seems like it’s been around forever, but the true origin of this one is a lot harder to pinpoint. John F Kennedy said, “Victory has a thousand fathers,” and that’s certainly true in this case.

Spoiler alert: there is no single source for the famous round, smiling face. But there is an interesting storyline filled with twists and turns, wars, borrowing, outright theft, corporate greed, and a long, strange trip through music history.

The more important question is: who popularized it?

Is there an original Smiley?

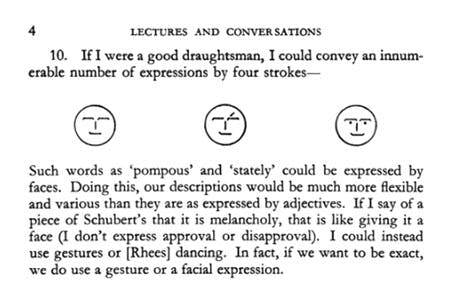

A symbol, a graphic, a design, an icon, an emoji: the Smiley is us. And such a pure visual expression of a face plus happiness that it springs naturally from the human mind at an early age, as most parents can tell you. Just add paper and crayons.

That means almost everyone–including you–can claim credit as being the originator of the Smiley face. Congrats.

But how did it emerge in popular culture? Who was the first to market the Smiley for commercial purposes? Who claims credit, who actually gets the credit, and who legally owns the rights to it? I'm about to let you know.

Who is the original creator of the Smiley face?

We begin in the small town of Worcester, Massachusetts, circa 1963, with a little-known freelance graphic designer named Harvey Ball, the man widely credited as the original designer.

A local subsidiary of the State Mutual Life Insurance company hired him to create a simple internal promotions campaign. The promotions director for the company, a woman named Joy Young, hired him to create a "smile button" designed to lift spirits and boost employee morale after a series of mergers and acquisitions.

Because apparently, buttons make everything better.

Types Similar to the artists I previously wrote about behind the ‘I Heart NY logo’ and The Rolling Stones ‘Lips and Tounge’ logo, they paid Harvey Ball just a small fee for his design: $45.

Sure, 45 bucks is a dinner and a movie these days, but in 1963 that comes out to around $370. And the work only took him about 10 minutes to complete. That's $37 per minute. Nice work if you can get it.

As he tells it, he first drew a simple smile but then realized people could easily turn it upside down–and into a frown. So he added the two dots for the eyes, picked a nice yellow color, and his job was done.

Now that's what I call being productive. I've spent more time looking for a pen.

This nonchalant approach might have been his stroke of genius.

“You can take a compass and draw a perfect circle and make two perfect eyes as neat as can be," Ball said. "Or you can do it freehand and have some fun with it like I did–to give it character."

What does the original Smiley Face look like?

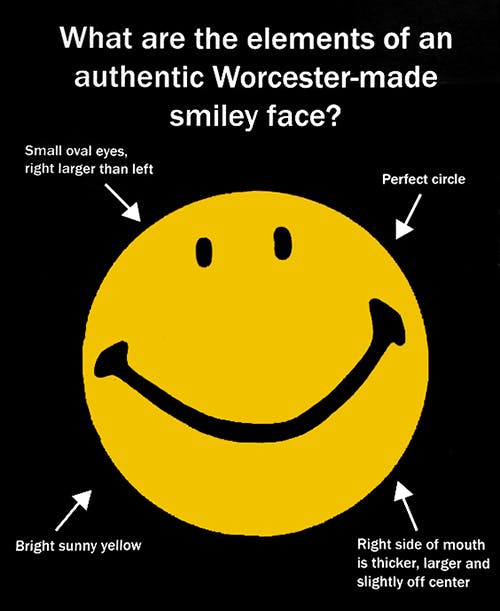

Although there have been countless iterations on it, the original Smiley has fairly distinctive characteristics that are pointed out if you ever visit the Smiley exhibition at the Worcester History Museum.

It's clearly hand-drawn, with a slightly crooked grin, two eyes fairly close together towards the top of the face, and the right dot slightly bigger than the left.

You may think these details are too subtle to notice or differentiate between other versions. But graphic designers obsess over this kind of stuff–and it can be the determining factor for authenticity if you're trying to sell an original on eBay.

If you have the real deal, you might even get 45 bucks for it.

What was the first Smiley used for?

Joy Young had originally commissioned Harvey to do the design to be printed on tiny buttons (at only a 7/8 inch radius) that would go along with the State Mutual company's "friendship campaign". As you might expect, they were a big hit.

Originally, they only produced only 100 pins. The next order was 10,000. Soon, Harvey Ball's Smiley appeared on posters, signs, desk cards, and other office materials.

Over the next few years, these cute little buttons made their way to other states and even Europe, bringing unabashed optimism wherever it went, in a time before things would take a turn towards cynicism and irony during the Vietnam war just a few years later.

In what seems like an oversight, neither Harvey Ball nor the insurance company bothered to copyright the design. But according to Harvey's son Charlie Ball, his father never regretted the missed revenue opportunity.

“He was not a money-driven guy," said Charles in an interview with the Telegram & Gazette. “He used to say, ‘Hey, I can only eat one steak at a time.'”

By other accounts, Harvey did eventually lament the decision.

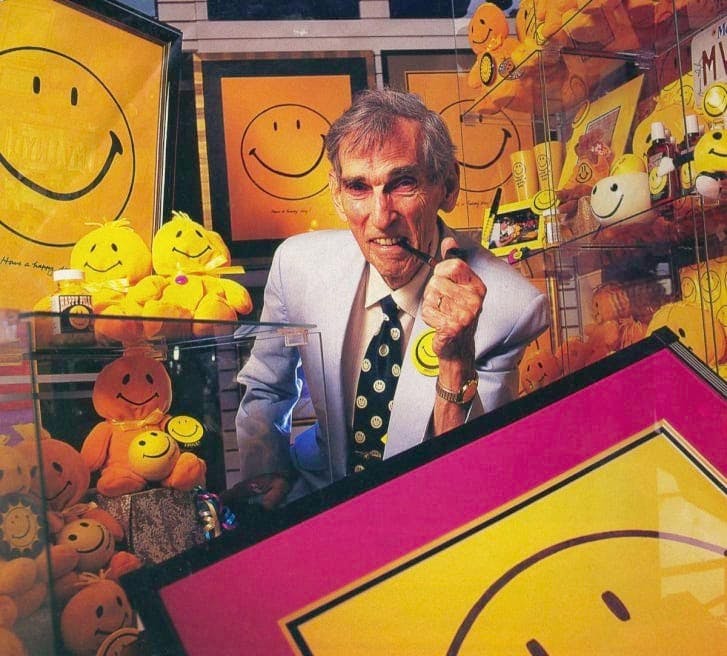

Who started the Smiley Face craze?

Fast forward to 1969-1970 in my hometown of Philadelphia, where two enterprising brothers named Bernard and Murray Spain represented the Hallmark company. They had two stores in the area and were on the lookout for marketing ideas that could help them boost sales.

At some point, they must have come across a Smiley button. Then they made it their own.

Types Based on the images I could find, the Spain brothers recreated the design in several variations, eventually settling on a more standardized and symmetrical look.

And just like that, the human touch of Harvey Ball's freehand design got left behind.

The brothers copyrighted a slightly revised version of the design along with the slogan "Have a happy day," which would later become the much more well-known "Have a nice day."

Bernard and Murray first started putting the image on packaging and other goods and immediately saw an increase in sales. Sensing a bigger opportunity, they started producing various branded items: pins, coffee mugs, bumper stickers, keyrings, clocks, cookie jars, and, of course, T-shirts.

Everything printed with the happy icon was selling like crazy.

Bernard and Murray's marketing efforts ushered in a two-year national fad that peaked around 1972. According to various sources I found, the Spain brothers sold a jaw-dropping 50 million Smiley buttons, along with a variety of other merch, generating over $1.5 million in sales.

Now that is something to smile about.

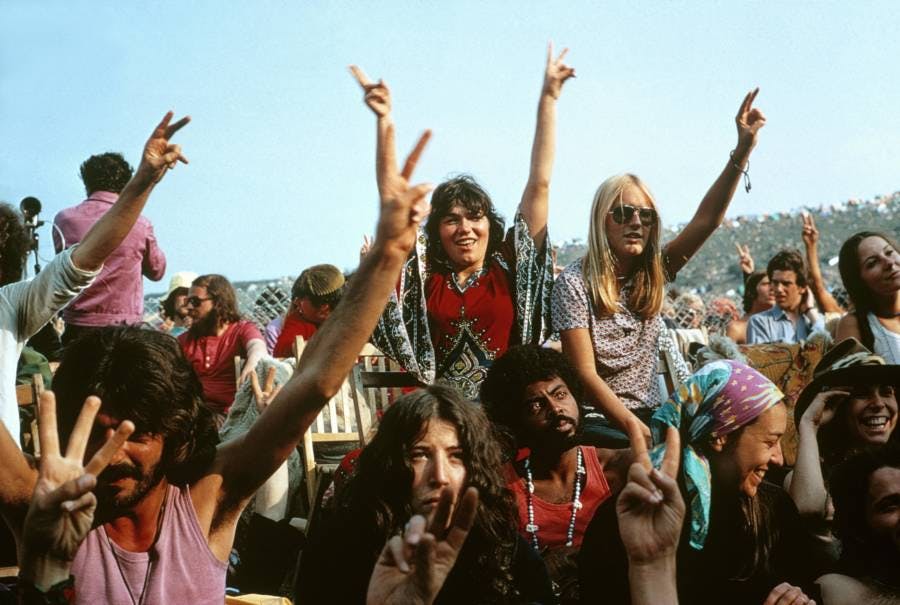

Part of the reason for the trend was the country's growing disillusionment with the current events of the time, including assassinations, distrust of the government, anti-war protests, and the civil rights movement.

As Jon Savage of the Guardian put it: "The fad hit the post-1960s mood: a traumatized American public turning to visual soma in order to forget the war in Vietnam and presidential meltdown."

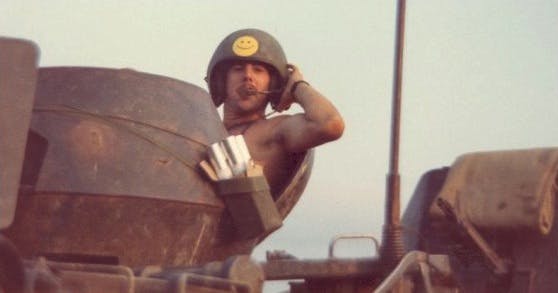

It's unclear whether the Smiley actually helped the nation regain its optimism during the Vietnam War, but one thing was certain: the positive message had already begun turning to irony. It famously adorned some soldiers' helmets fighting in the war.

At least their enemies got to see a little happy face right before they died.

Harvey Ball's simple creation had traveled all around the world and back.

It was the Spain brothers in Philadelphia who first catapulted the Smiley towards becoming one of the most recognizable logos of all time and provided an icon for those wanting to promote positivity in the face of uncertainty and dark times.

"Our only desire was to make a buck," says Murray. "But when it became accepted as a symbol of happiness, we were thrilled."

It also became a symbol of consumer America, stamped on everything from cheap plastic trinkets to upmarket goods sold in swanky department stores such as Bergdorf Goodman on Fifth Avenue in Manhattan.

Murray and Bernard soon became minor celebrities known as the "Smile Brothers."

Throughout most of this time period, Bernard and Murray never claimed to come up with the design itself, which they acknowledged was the creation of Harvey Ball. Except for one time on the national television show "Whose Line Is It Anyway?" when they publicly took credit for it.

The Spain brothers deserve the credit for kick-starting the craze in the United States and abroad. But in the same crucial oversight, they failed to take the logical next step: trademarking the design.

Who owns the rights to the Smiley Face?

Around the same time, in 1971, an enterprising young French journalist named Franklin Loufrani skipped college to join his first newspaper at 19 years old. He was known for his entrepreneurial spirit and as "a marketing guy always coming up with new stuff."

And he certainly saw the marketing potential of a little yellow happy face.

As the story goes (according to him), he had become fed up with all the downer news stories and negativity, and so he came up with the symbol to label positive news stories for readers.

Yes, you read that right–Franklin denies Harvey Ball the credit. He always insisted the symbol was too basic to credit a single person with its invention.

Never mind that his Smiley looks almost identical to the face created by ol' Harvey Ball.

Smiley published in the newspaper France-Soir, in 1972.

Loufrani started a campaign to highlight happy news stories and, in 1972, published his first Smiley in the paper France-Soir. Once again, Smiley captured the public's imagination and yearned for happiness.

But Franklin did something that those before him failed to do. He trademarked the design.

Thus, a brand was born, and the symbol was dubbed the Smiley.

He launched a company and vowed to "harness the power of positivity” and began the enterprise by selling Smiley T-shirt transfers. And frisbees. Lots and lots of happy frisbees.

Then came his masterstroke: licensing.

The concept of licensing, or allowing other companies to use your logo in exchange for a percentage of every sale, wasn’t a popular business model in Europe at that time, and he may have been one of the early entrepreneurs to exploit that space.

It seems he was French by birth but American at heart.

After Smiley appeared in the France-Soir, other leading European newspapers wanted a piece of the positivity he was selling, which reminded people to "take time to smile.” And they were willing to pay to use it.

Loufrani, like the others before him, knew this was a big deal and, with a trademark in hand, capitalized on it in a way no one else had done yet: tapping into a movement.

Peace, love, and Smiley business

During the early '70s, France was having a counter-culture moment similar to America's hippies: young people were rejecting traditional norms and moral structures, embracing the concepts of free love and a cultural revolution.

Loufrani took a radical step himself, printing 10 million stickers and handing them out for free at festivals, concerts, and in the streets. The simple joy conveyed by the graphic tapped into the zeitgeist of the time, making it the symbolic figurehead for happiness, peace, and activism.

Was Loufrani himself part of the movement? Not that I can tell. Or at least he never claimed to be. He was all about the Benjamins (or whatever the French version of that is).

As his son, Nicholas, admitted: "You could say there was a political or social meaning behind what he did, but it was really a commercial act. He wanted to make money on it."

As the love spread and Smiley made a home for itself next to the peace symbol on jean jackets and bellbottoms around the western world, brands came a-knocking.

And Mr. Loufrani was there to greet all of them.

His licensing company became a global empire worth more than $500 billion a year, with its tentacles wrapped around the world, supplying Smiley rights to hundreds of companies over several decades and squashing competition and copycats wherever found.

Apparently, there can be only one.

Loufrani's Smiley (left) vs. Harvey Ball's original (right).

Oddly enough, on the Smiley company website, they don't even mention Harvey Ball. Only the design "was born in the '70s" before Loufrani adopted it. Their marketing spiel credits themselves with harnessing "The power of positive propaganda." Not kidding.

But was it born in the '70s? Let's go back in time, back before the humble Harvey Ball, to an even more innocent period in Smiley face history.

Earlier versions of Smiley?

In the science world, there is a principle called "multiple discovery," which is also known as "simultaneous invention." The idea is that several independent people can reach the same breakthrough or invention around the same time because the conditions are ripe.

And that the same theory can apply to art and design.

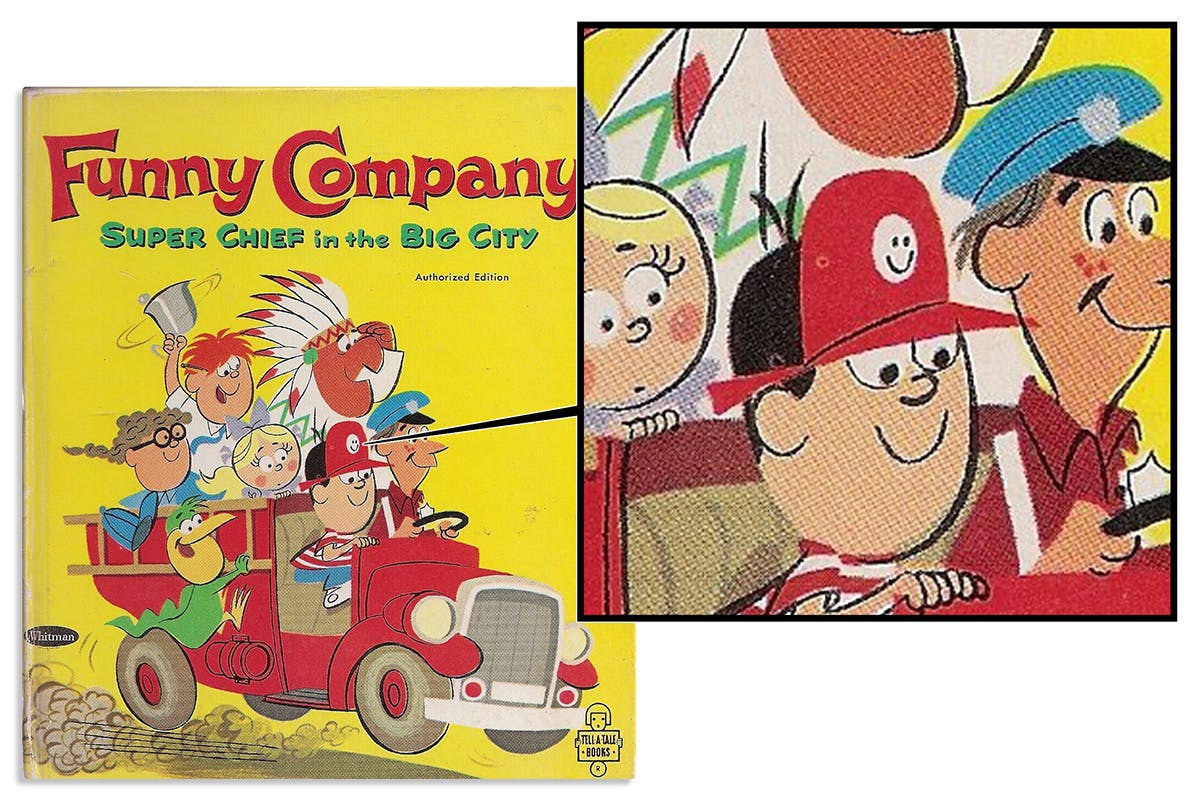

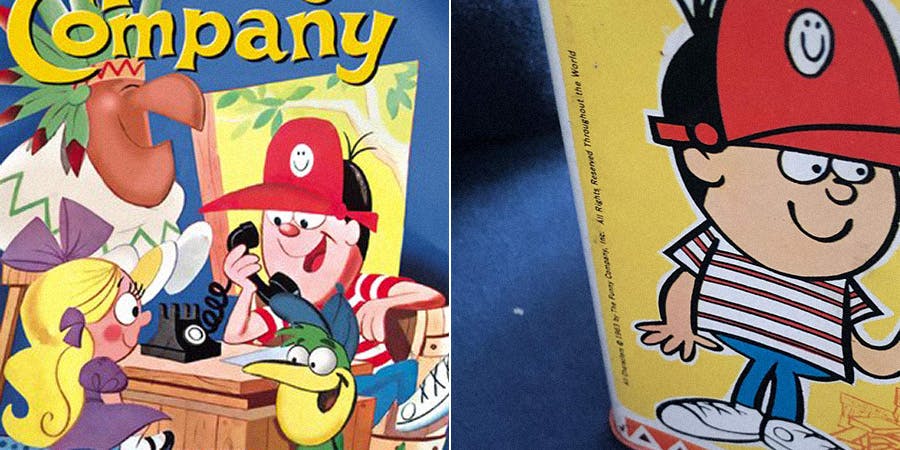

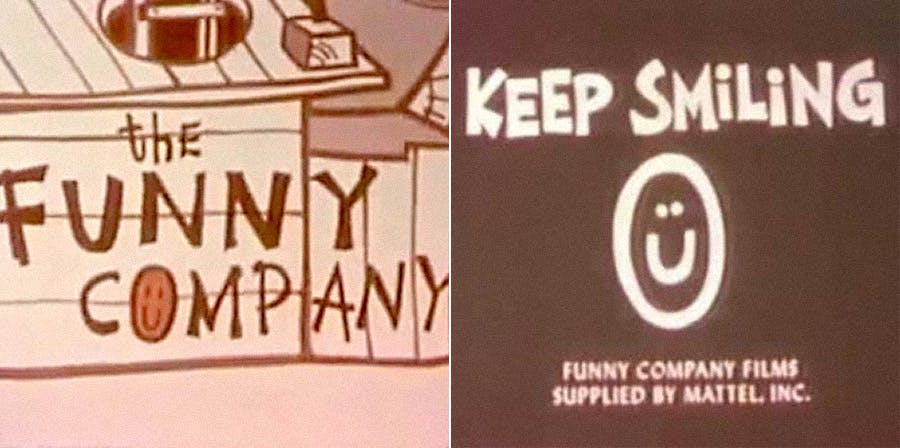

Smiley face in The Funny Company

Although the creation is widely attributed to Harvey Ball in late 1963, that little happy face was already on TV.

In a 1963 children's program called The Funny Company, the main character's cap had the distinctive two-dot-no-nose Smiley displayed prominently. Other characters wore the same cap in various cartoons, and it appeared all over their ads and merchandising.

If that's not enough, the Smiley was often right in the logo as the “o,” and they ended the episodes with the Smiley by itself, along with the tagline “Keep smiling!"

You can’t help but wonder if this is how it seeped into Harvey Ball’s consciousness while his kids were watching the cartoons on TV. Or maybe he was a big fan of the cartoon himself.

So that must be the first one, right? Even before T-shirts?

Not so fast. Ever hear of The Good Guys?

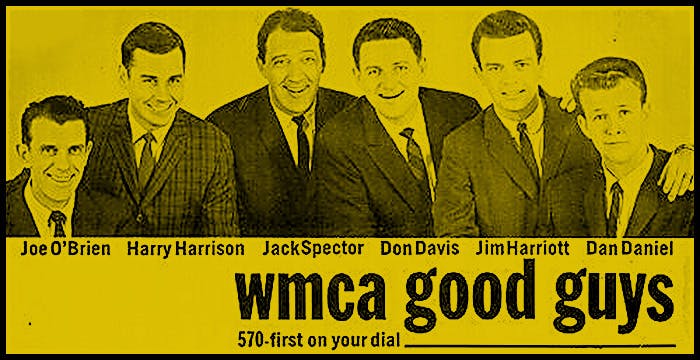

The Good Guys Smiley Face

If we go back in time one year to 1962, the New York Radio station WMCA had a marketing campaign for their broadcast team “The Good Guys” and they gave away thousands of gold sweatshirts that were printed with the words “good guy” along with… you guessed it: a Smiley face.

When the station called listeners if they answered their phone “WMCA Good Guys!” they got rewarded with one of the distinctive sweatshirts: always gold, always with the Smiley face printed in black.

Although it had more of a hand-drawn look and was decidedly oblong, there’s no question it was a direct precursor to the Smiley we know. These shirts were so popular that they became synonymous with 1960s culture in New York City.

So was that the first? Or at least the first one printed and used for promotion?

Funny you should ask.

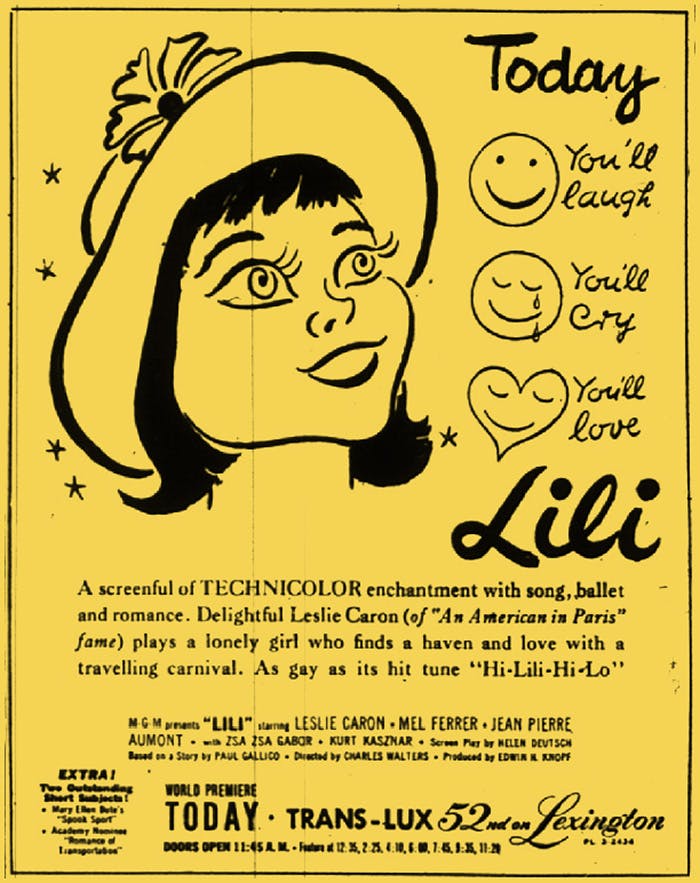

Promo poster for the movie Lili, 1953.

Smiley Face Lili

Jump back in time almost a decade to 1953 and you find this promotional poster for a major MGM movie called Lili. Not only do we have an almost perfect, distinctive hand-drawn Smiley face, but we also have a cry face and a heart Smiley face.

Did this artist invent emojis almost 50 years before they appeared on computers? Nope–emojis appeared before that, which we’ll get to.

This is the only instance of these Smiley faces I could find among the promotional materials for the movie, so I’m not sure how widespread the distribution was. But that Smiley is spot-on.

Surely we must be at the end of the line? Well…

Smiley Face Jug

Jump back a few thousand years in time to ancient Turkey, when they apparently drank out of big teardrop-shaped pitchers.

In 2017, archeologists dug up this old ceramic jug and when they assembled it they discovered it was decorated with that distinctive two dots and a curve–a Smiley face. From 1700 BC.

Nicolo Marchetti, who led the excavations, calls it “the oldest smile of the world.” You can go see the artifact at the Gaziantep Museum of Archaeology, where it continues to smile to this day.

Luckily for the Smiley Company, the Hittites aren’t around to collect any royalties.

Smiley goes dark

Jumping back to where we were in the timeline, it’s 1972 and the first wave of the Smiley craze was reaching its zenith. In the space of just two years, the Spain brothers had raked in $1.5 million selling Smiley merchandise, and Franklin Loufrani had injected the symbol into youth culture and locked in hundreds of lucrative licensing deals.

And this is around the time when things started taking a turn.

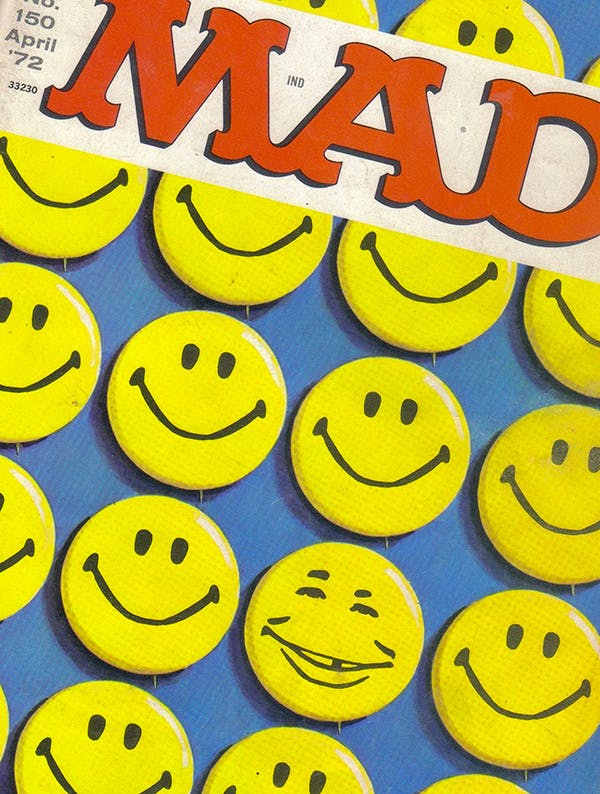

Alfred E. Smiley

In April 1972, the legendary satire publication MAD Magazine featured the first parody version of the Smiley on its cover, marking the end of innocence for the symbol of happiness.

As popular as it was, Smiley culture was overshadowed by the horrors of Vietnam and the increasingly violent war protests back home, both of which were escalating even as attempts were being made to end both.

The time was ripe for the subversion of Smiley’s meaning and its appropriation in different media.

Mad Magazine featuring Smiley on the cover, 1972.

On the cover image, one of the Smiley pins bears the conspicuous features of Mad’s mascot Alfred E. Neuman, whose trademark gap-toothed smile has a history of its own.

Given the satirical nature of the magazine and the cultural context of this time, Alfred’s ignorant catchphrase “What, me worry?” superimposed onto the Smiley seemed to imply that yes–you should worry.

Boss Smiley

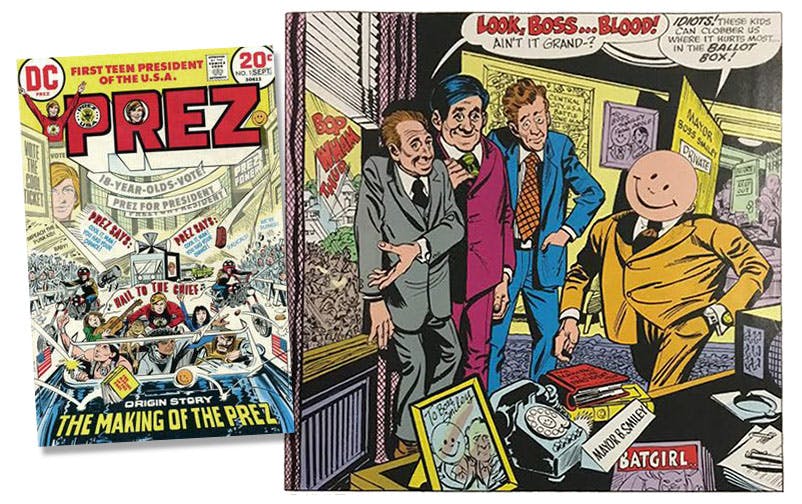

In 1973, DC comics pushed a short-lived series called Prez by Joe Simon, the legendary creator of Captain America, which imagines the first teenage President of the United States. In issue #2, the title character Prez Rickard battles Boss Smiley: a corrupt, all-powerful political boss with the head of a Smiley-face button.

The comic was stridently political and satirical, speaking to the turbulent nature of the time, and Smiley, as a villain, reflected the public’s growing disillusionment and a distrust of authority.

We’re not buying the old Smiley-faced routine, it seemed to say, we can see through you. Instead of representing happiness, Smiley represented shady corporate greed and political power.

Although the comic was unsuccessful, lasting only two years, it made an impact in the public consciousness, and especially with other comic book creators, who would reprise some characters in future comics over the years–including Boss Smiley.

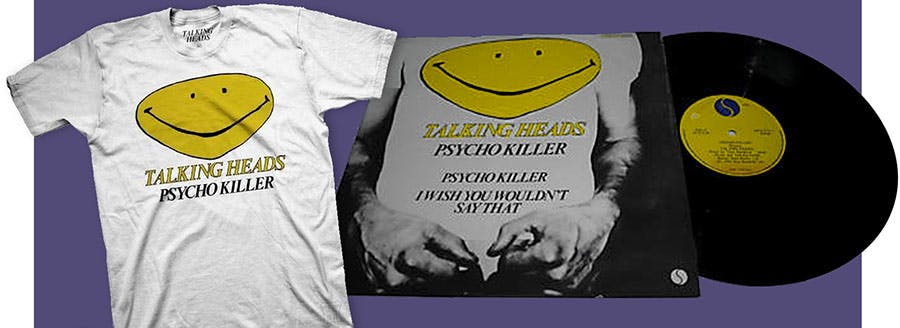

He would appear over 40 years later in issue #54 of Neil Gaiman’s blockbuster series Sandman, which features a bleak retelling of the Prez story and imagines Boss Smiley as an evil, god-like figure. Apparently, that old cynicism dies hard.

Boss Smiley appears in the Sandman comic (2015).

“He’s the CEO of Smiley Enterprises,” said writer Mark Russell. “In the future, under the corporate personhood amendment, corporations are not required to reveal the identities of their corporate officers. So Boss Smiley wears the smiley face mask to conceal his personal identity as the CEO of Smiley Enterprises.”

Psycho Killer Smiley

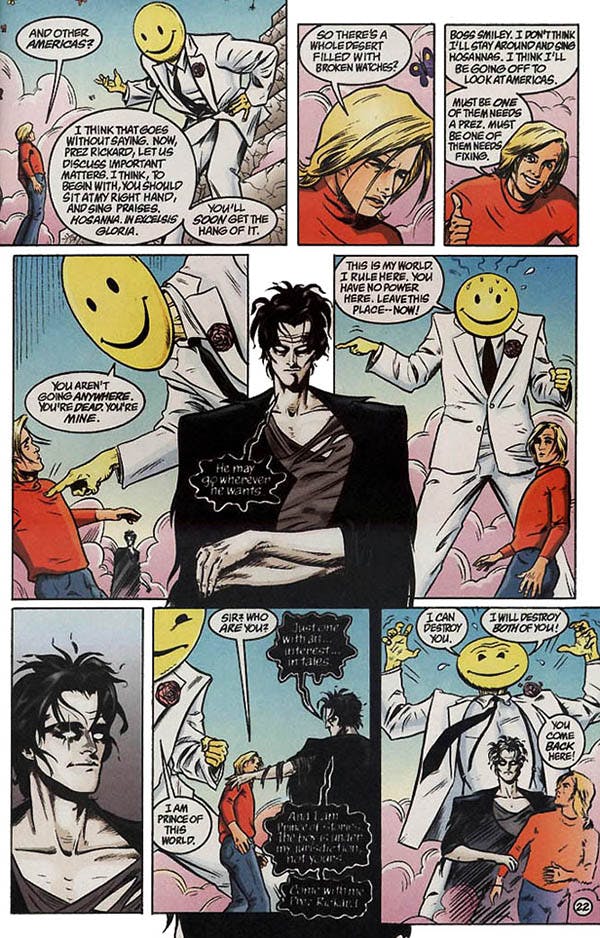

Back to the ’70s and the beloved and influential rock band Talking Heads made a massive splash with their debut release. The title track and debut hit on their first album was the funky new wave song “Psycho Killer” which would later be included in The Rock and Roll Hall of Fame’s 500 Songs that Shaped Rock and Roll.

On the 12” single release in 1977, you can guess what they pictured on the album cover. Someone wearing a T-shirt with a distorted version of the Smiley face. Quite the dark place to see the symbol for happiness hanging out.

Was the song about an actual psycho killer?

“Psycho Killer” became instantly associated with the Son of Sam serial killings, which were happening around that time. Although the band always insisted that the song had no inspiration from those particular events, the single’s release date seemed eerily timed.

Also, the lyrics seem to represent the thoughts of a serial killer.

In the liner notes of Once in a Lifetime: The Best of Talking Heads, Byrne says: “When I started writing this, I imagined Alice Cooper doing a Randy Newman-type ballad. Both the Joker and Hannibal Lecter were much more fascinating than the good guys. Everybody sort of roots for the bad guys in movies.”

A psycho killer wearing a happy T-shirt ironically. The “good guy” is really a bad guy. A wolf in sheep’s clothes. Happiness as madness. It’s almost like Smiley became a teenager.

The Nazi Smiley

Speaking of debut albums that took the Smiley to dark places, in 1979 legendary punk rockers The Dead Kennedys released their first single, entitled “California Über Alles”, an allusion to a removed part of the German National Anthem associated with the not-very-happy movement known as Nazism.

The album cover, designed by Bob Last and Bruce Slesinger, featured a modified image from that time period, but instead of Hitler it was the governor, and instead of Nazi symbols, it was Smiley faces. Complete with a photocopied look that helped define punk.

As for the political message of the design, any comparison with Hitler is bound to be heavy-handed, but punk is not known for subtlety. And the Smiley-as-Nazi symbol is just as over-the-top, in that it completely flips its meaning.

In less than a decade, the Smiley had gone from love and happiness to irony and cynicism.

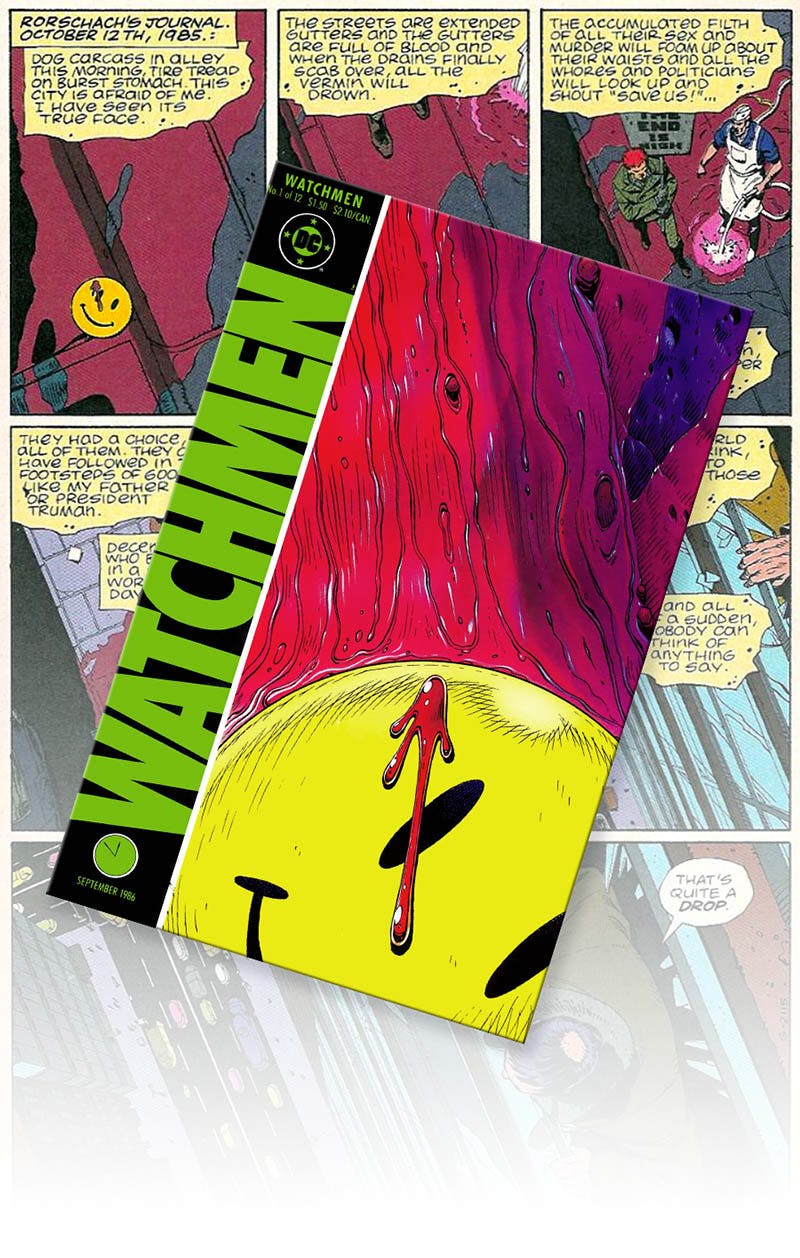

The Watchmen Smiley

In 1986 the Smiley returned to the pages of comic books in Alan Moore’s breakthrough series The Watchmen, which, along with being widely praised and critically acclaimed, would achieve legendary status among comic book fans.The Smiley face is a reoccurring symbol throughout the books and is featured on the cover, notably tilted and blood-stained.

The books revolve around a team of somewhat anti-hero superheroes in an alternate history that imagines the United States winning the Vietnam War and the Watergate break-in never exposed.

The Watchmen series comes with its own set of contemporary anxieties as the country is on the brink of war with the Soviet Union, and focuses on the moral struggles of the protagonists as it deconstructs and satirizes the superhero concept. In a retrospective review, the BBC’s Nicholas Barber described it as “the moment comic books grew up”.

In the story, a costumed vigilante character named Rorschach investigates the murder of a government-employed superhero named The Comedian after finding his signage Smiley face pin splattered with blood. It’s notable that the most corrupt and violent superhero wears the Smiley.

The symbol is so pervasive in the series that it even appears on Mars, where the characters Jon and Laurie end up in the midst of a rock formation shaped like a Smiley.

Life imitated art in early February of 2008 when a big Smiley was spotted on the face of the red planet by an orbiting satellite. The following year, the major motion picture “The Watchmen” was released.

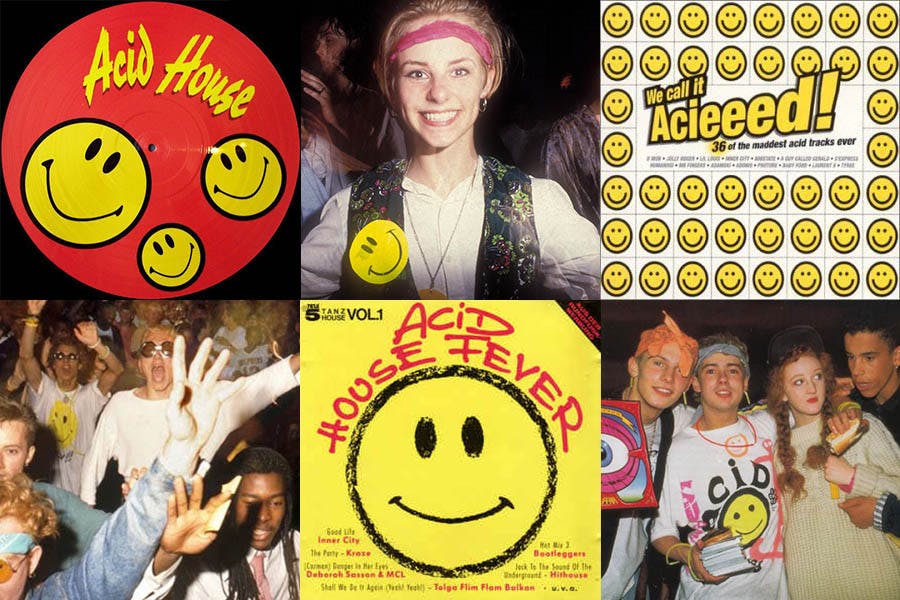

Smiley Goes Raving

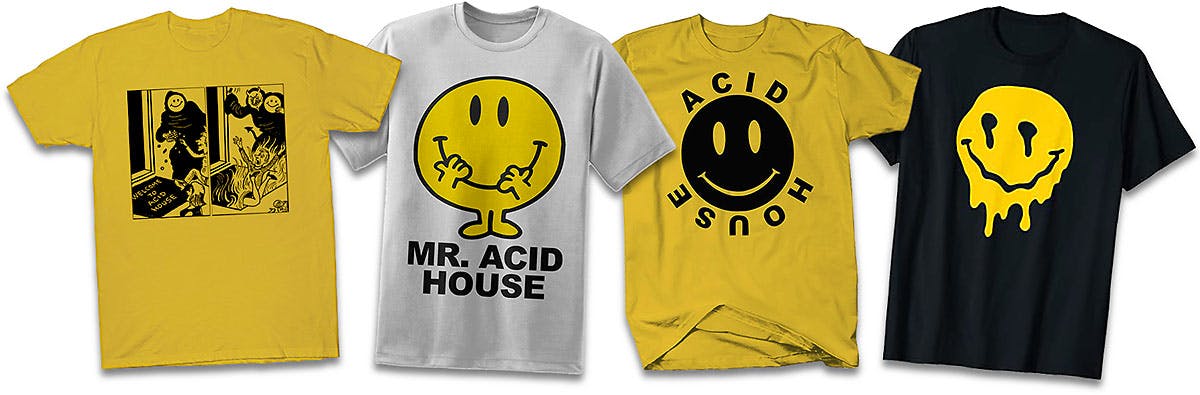

Two years after the Watchmen, as if an antidote to the dark period in the life of the Smiley, a burgeoning music culture appropriated the symbol in the UK, returning to its simple roots in both the graphic style and what it symbolized: happiness.

Acid House Smiley

The new music genre was called Acid House, and the Smiley was almost instantly synonymous with the sound and the parties. The year 1988 became known as “The Second Summer of Love”, taking a cue from hippies almost exactly two decades earlier.

This time, although the spirit of the Smiley was revived, the music and the vibe of these events were different.

Acid House music was upbeat and celebratory rather than sentimental and politically charged, and it confined the reveling that took place to dark warehouses in early morning hours rather than daytime festivals in fields.

How did this come about? To make a long story short, in 1987, some London DJs discovered an exclusive club on a remote farm called Amnesia while on holiday in Ibiza, a town famous for international jet-setting visitors and non-stop parties.

Inspired by DJ pioneers like Frankie Knuckles, Marshall Jefferson, and DJ International, who played American “house music” from Chicago, they took this epiphany back home with them.

Soon, this handful of DJs was attempting to recreate the experience in London and other cities.

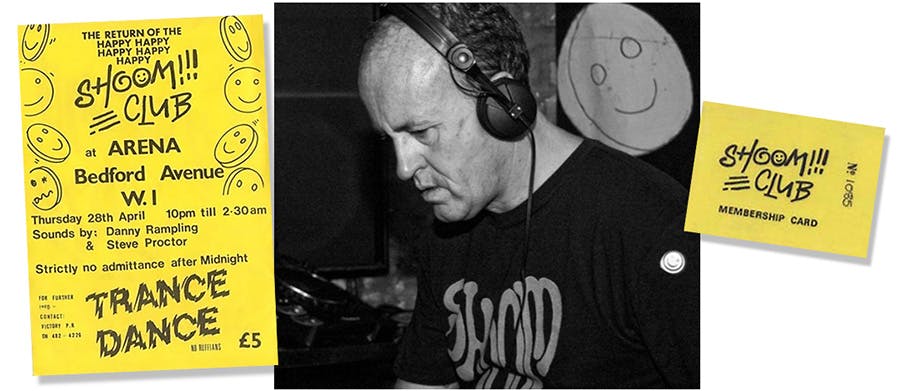

One of those DJs was Danny Rampling, who started throwing a club night with house music called Shoot, which became insanely popular. The Smiley face as the defining image of acid house was born, as the symbol infused into the logo, the flyers, the decor, and clothing.

Although most of the music was coming from the gritty and diverse underground dance music scenes of Chicago and New York, the UK promoters and party-goers were putting their own exuberant spin on it, and in 1988 the scene exploded, leading to full-blown raves and a decades-strong, worldwide electronic music culture that continues to this day.

Rampling says he got the idea from seeing someone at a club wearing a shirt covered in Smileys, but there was another, possibly more obvious, inspiration.

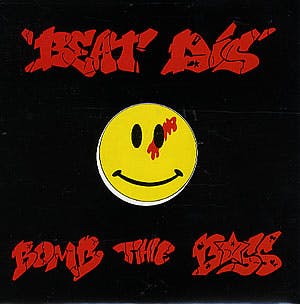

Bomb The Bass Smiley

Also in 1988, a certain sample-heavy record was getting lots of play by the DJs at some of these clubs. “Beat Dis” by British producer Bomb The Bass featured our good ol’ Smiley face on the cover, and many credit this record as the origin of the acid house Smiley. On some releases, it even had the blood splatter–clearly a reference to The Watchmen.

The record was a big hit around the world, peaking at #2 on the UK Singles Chart, and reaching #1 on the US Billboard Hot Dance Club Play chart for a week. There are over 25 different samples used in the track, ranging from Afrika Bambaataa to James Brown to Aretha Franklin, Prince, Public Enemy, and Philadelphia’s Schooly D.

The song epitomized the emerging cut-and-paste aesthetic in electronic dance music, and the Smiley provided an instantly recognizable icon that was cut and pasted from graphic design history to go along with the fresh and exciting sound.

But did the Bomb the Bass Smiley predate the Club Shoom Smiley?

If Rampling’s story is true, and he decided on his logo before he saw this record, he must have been overjoyed when he got it. Because you know he had to have been playing it. Perhaps everyone around that time was appreciating the Smiley again.

They say fashion trends come in twenty-year cycles. And like all trends, it came and went.

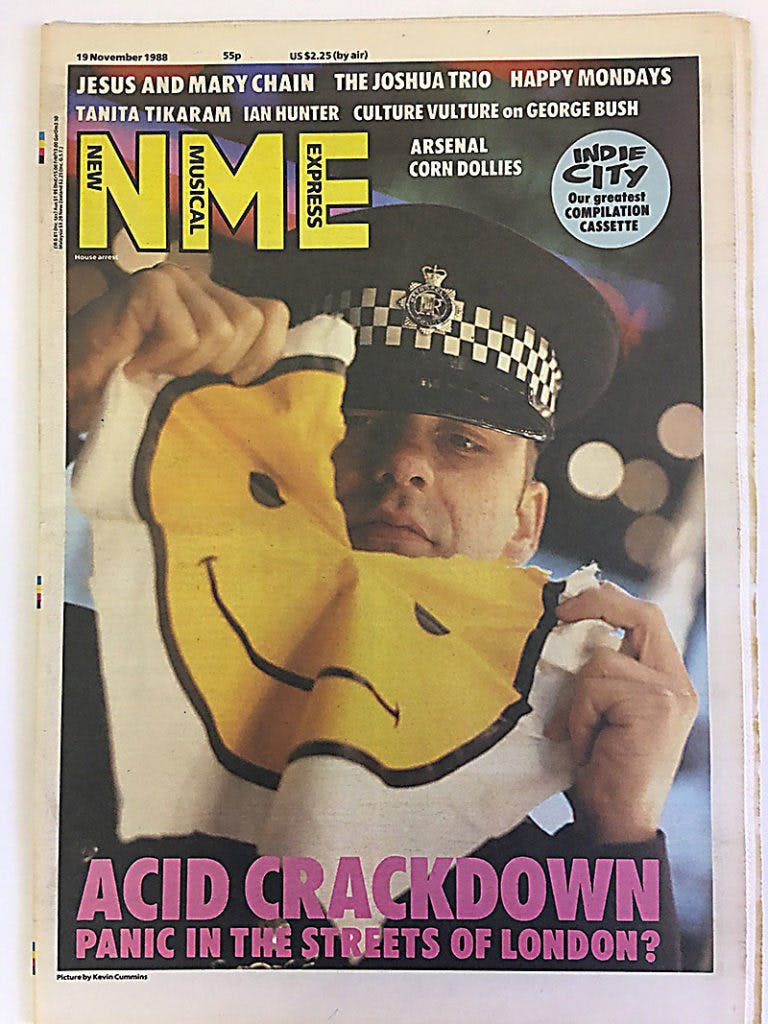

Cracking Down on Smiley

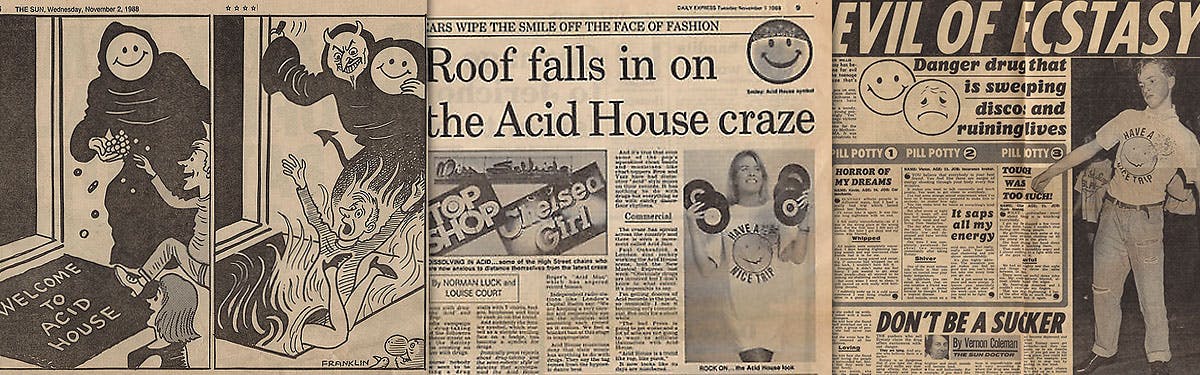

Like a condensed version of the Smiley’s initial trajectory from innocence to cynicism, the initial exuberance of this music scene turned dark within a year or two. By 1989, major newspapers sounded the alarm about the decadence that was going on at these late night clubs–complete with Smiley faces in the front pages–causing a moral panic, and soon the police were cracking down, turning that smile upside down.

The Smiley’s ride with Acid House has risen and fallen along with the music’s popularity, but perseveres as its symbolic mascot and remains steadfastly un-ironic and earnestly happy–even if it’s warped or, shall we say, chemically enhanced?

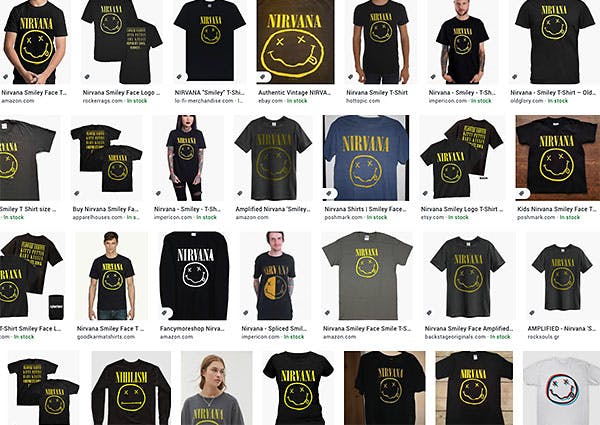

Smiley Goes Grunge

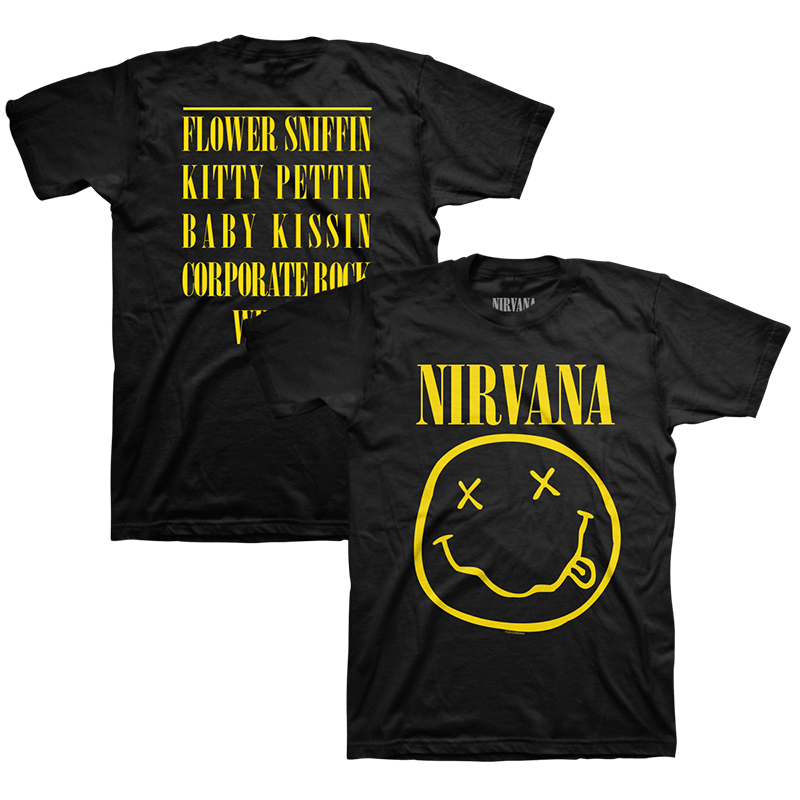

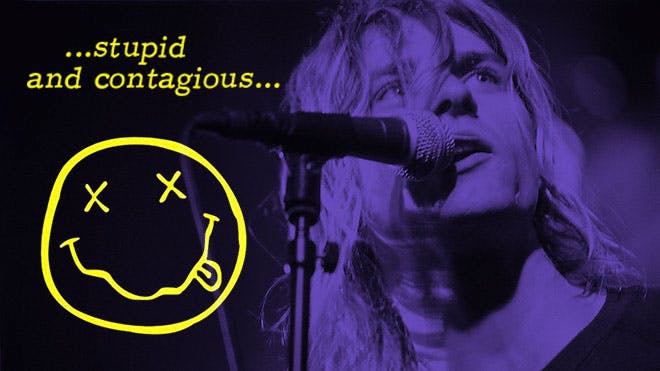

Jump ahead two years and across the pond to Seattle, where a little band you may have heard of released their multi-million-selling breakthrough album Nevermind in 1991. Nirvana had been playing small shows around the Northwest scene for a few years and had already released their debut album in 1989, making a name for themselves locally.

But nothing prepared them (or the rest of the world) for their phenomenal, genre-defining, and instantly classic second album. And along with the unforgettable cover art, their Smiley design– with its ex’d out eyes and lolling tongue– became one of the band’s enduring images.

In the early ’90s, you couldn’t go to any rock concert or mall without seeing the T-shirt.

According to people who keep track of this stuff, the late great Nirvana frontman Kurt Cobain drew the logo, which was first seen on a flyer for their album launch party at a Seattle bar in September 1991, and the T-shirt printing begun by the end of the year.

Was this yet another subversion of the Smiley? Yes, but it’s probably not that deep.

Although their music was, in part, a rebellion against the more polished, commercial sound that predated it, the design seems about as deep as something you would see doodled on a book cover. It’s a Smiley, but he’s wasted. Get it? Or maybe happily dead. In hindsight, and after his untimely and tragic death, it seems morbidly à propose.

Some people say that it was a similar Smiley that was a constant fixture on the marquee of the notorious Seattle strip club The Lusty Lady that had inspired him. The tongue sticks out and the eyes look zonked out (ogling?) but who knows.

But as I mentioned at the beginning, we’re talking about a simple design that countless others have probably drawn. I could probably find something similar in my sketchbooks. The difference is that Nirvana blew up, and everyone wanted a piece. You could say it was…

Nowadays, you can get your own T-shirt from the Nirvana store. Or you can get one from Walmart, Target, Amazon, eBay, Urban Outfitters, and hundreds of other online stores.

You can also get a bizarre variety of other branded items, including seat belts, stress balls, baby onesies, license plates, shower curtains, lamps, “best friends” necklaces, and an air freshener.

Probably not what Kurt Cobain had in mind, but hey. Merch gotta merch.

The design is so ubiquitous that it gives the original Smiley a run for its money. And people have cashed in. Does the following image look familiar?

In 2018, the fashion brand Marc Jacobs put out their take on the famous design, which says “Heaven” rather than the band name, with an “M” and a “J” for the eyes.

Nirvana LLC, the company formed by surviving band members Dave Grohl and Krist Novoselic, sued the fashion designer (along with Saks and Neiman Marcus) for copyright infringement.

To my eyes, it’s clearly a rip-off. And not the first time Marc Jacobs has done it. But that will be up to the courts to decide.

As of this writing, after years of going back and forth, the two sides are still battling, while a new claimant has jumped in the ring: a former art director for Geffen Records who now claims that he drew it. It’s a whole mess.

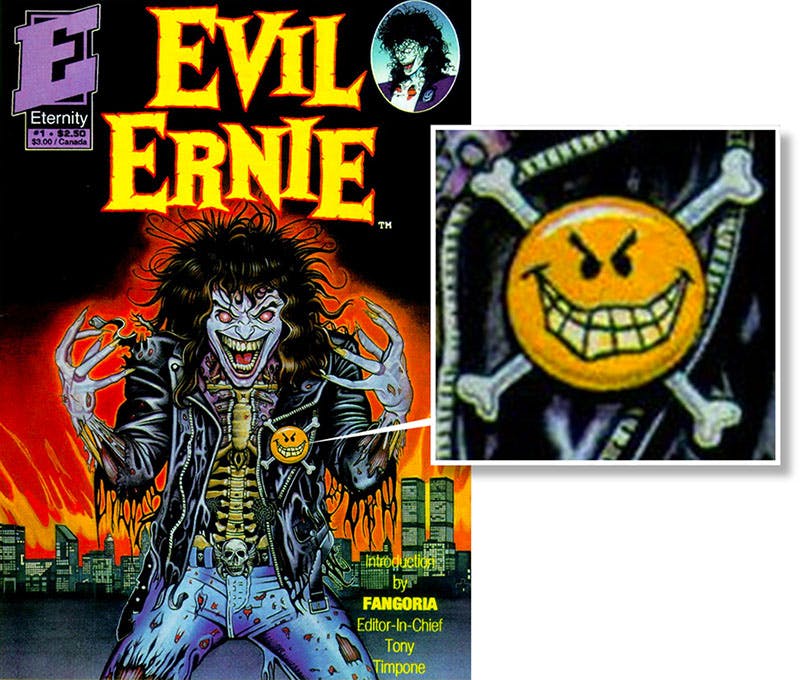

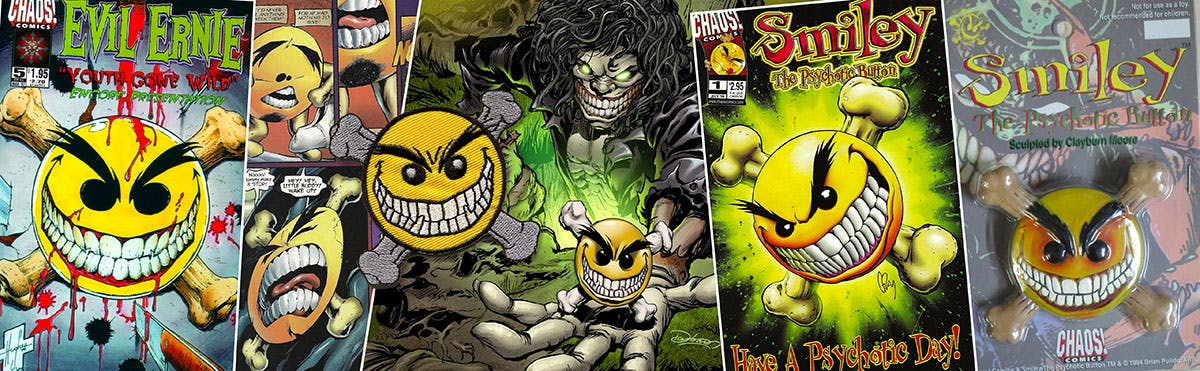

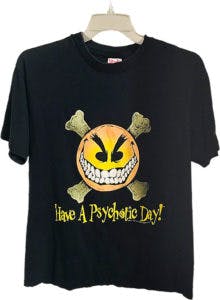

Smiley Turns Evil

In 1991, around the same time, an independent horror comic debuted called Evil Ernie. The main character, “Evil” Ernie Fairchild is an undead teenage psycho killer with the power to make sketches come to life.

Oh, and he wants to cause megadeth (getting the world to unleash all of its nuclear weapons on itself). You know, happy stuff.

Anyway, Ernie’s partner/sidekick is an evil, wise-cracking Smiley born from his pet rat (don’t ask). The Smiley is pinned to his jacket, giving him powers and providing comic relief. It achieved cult status, gain a vast fan base in the comic community, change publishers, and get revived more than once. Like you’d expect from the undead.

Smiley The Psychotic Button, the evilest and most subversive version of our beloved Smiley yet, becomes the star of the series in later issues. He can move around freely and control the dead, with some kind of weird new back story about a guy named Richard whose soul gets infused into a Smiley button. It’s a whole thing.

The Evil Ernie comic book series started with Eternity Comics, then moved to Chaos, then Devil’s Due, and finally Dynamite Comics. The last published issue I could find was in 2016. Twenty-five years is a hell of a run for such humble beginnings, and creating its own iconic Smiley definitely earns it a place in Smiley history.

Will Evil Ernie and his Psychotic Smiley get revived from the dead again? A better question might be: when is the movie?

Smiley gets a fake origin story

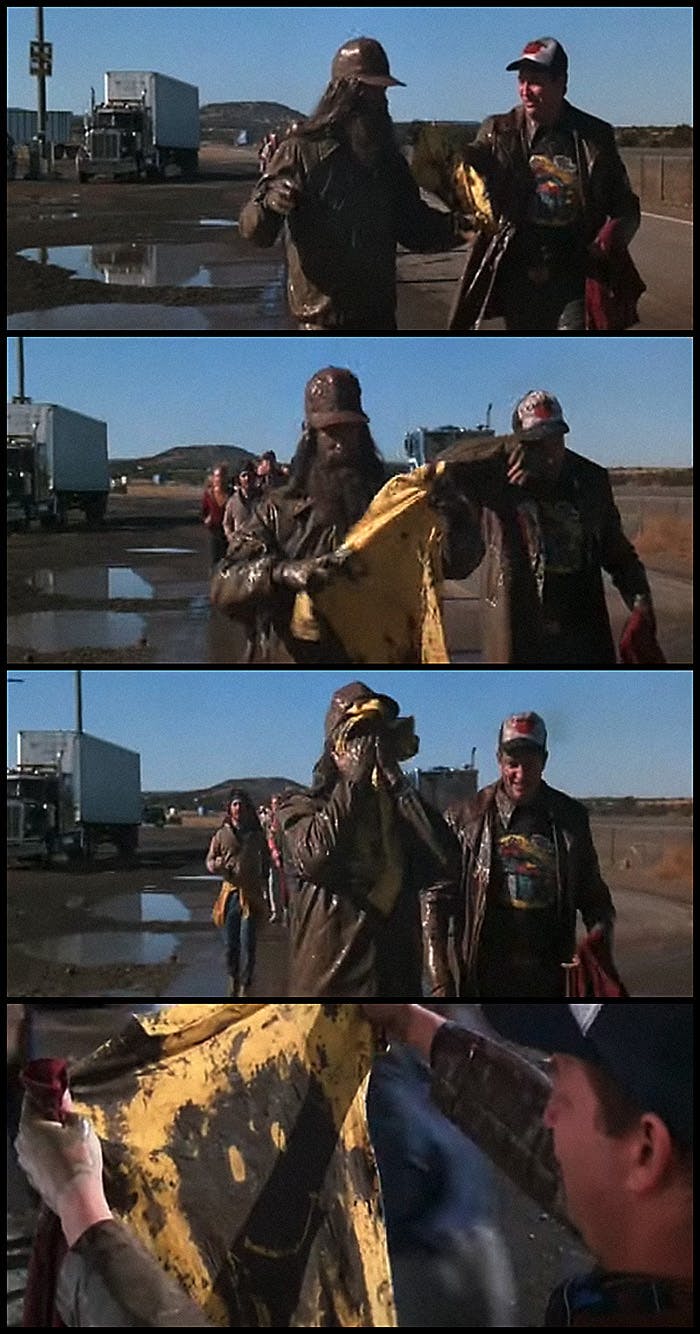

The 1994 movie Forrest Gump provides an entirely fictional origin story for the Smiley face. With the movie becoming such a colossal hit, and the public’s lack of knowledge of the genuine history of the Smiley face, it’s become cemented in people’s minds.

In the scene where a mud-caked Forrest is running a race, an enterprising T-shirt salesperson offers him a clean yellow shirt, he wipes his face, and the rest is movie history. “Have a nice day!” says Forrest.

But like everything else in that movie, it’s made up. And it’s entirely possible that some percentage of the population thinks that the actual story is something similar to the movie. If only someone would write the true story of the Smiley Face T-shirt 😉

Smiley joins the next generation

In 1996, Franklin Loufrani was getting old and so was the smiley business. Licensing deals had played out, and the public seemed more interested in Tickle-Me-Elmo and the Macarena. Loufrani passed control of the business to his son Nicolas, who was only 26, and initially less than enthused. He thought of it as a licensing play whose time had passed.

“There was no brand name, no company — just a logo,” Nicolas said. “In the US, people would call it a ‘happy face.’ In France, it was a sourire. In Japan, it was a ‘peace love’ mark. Every country had a name for it. So I decided, okay, we need a brand.”

Nicolas, with his father’s blessing, took over The Smiley Company™ and began forming his own designs for the future of the brand, securing trademarks in over 100 countries around the world. They already owned many of them, and where they didn’t, they bought it–or fought for it, often battling business owners in court. Including the retail behemoth Walmart.

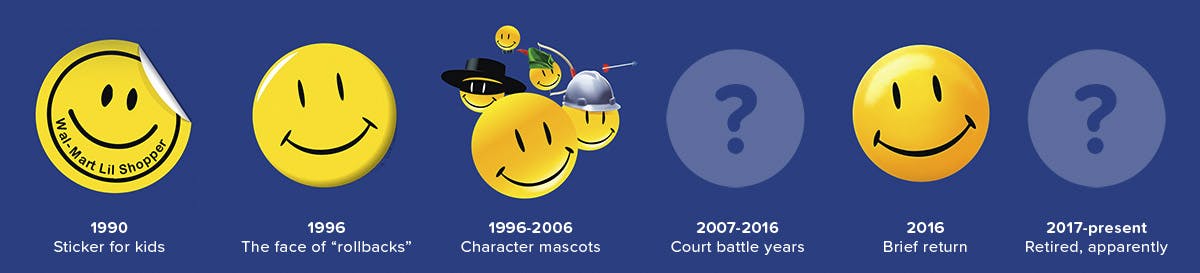

Smiley goes corporate

Around the same time in 1996, the Walmart Corporation rolled out “the new face of rollbacks”. It was a smiley with a button-like look. Walmart had already been using a smiley face on stickers since 1990, made for giving to kids (“Lil’ Shoppers”) on entry. Start them early, I guess.

They unleashed this shiny new smiley “to signify falling prices” because obviously. It was used in ad campaigns and in-store signage as a sort of mascot for Walmart and would become 3 dimensional and elaborate over the years, donning hats and costumes and bouncing around in commercials.

It was a happy time for profiting from cheaply made goods.

Around 2001, notably after the events of Sept 11th, Walmart Smiley stopped making appearances in commercials. By 2006 it had disappeared completely from box stores and blue vests across the country. What happened?

According to Walmart spokeswoman Danit Marquardt, “He didn’t fit in with our advertising at the time. We were taking a different approach.” Okay, but what really happened?

The Walmart Smiley in 1996 (left) and its brief return in 2016 (right).

Smiley goes to court

Rewind back to 1997. Nicolas Loufrani filed a trademark application in the United States to put his Smiley Company brand all over stationery, plush toys, mugs, T-shirts, and more. Walmart opposed the registration–setting up one of the biggest intellectual property showdowns in modern history.

It was Smiley vs Smiley in a legal battle that lasted over 10 years.

Although Loufrani put up a valiant fight, the Trademark Trial and Appeal Board eventually sided with Walmart. Because how else would people get signified about falling prices?

Not to be defeated, Loufrani sued Walmart in federal court, claiming his Smiley was clearly distinguishable from theirs–even though it looked exactly the same.

Finally, they announced a confidential settlement agreement in 2011. Afterward, both sides declared victory.

So did Walmart cave? Or did Loufrani give up?

All we know is that in 2016, Walmart briefly re-introduced their low-price Smiley mascot to minimal fanfare, before it disappeared again. Meanwhile, Loufrani continued on his mission to turn the world into a giant Smiley face–and rake in all the profits. He never slowed down.

Smiley goes digital

Around 1998, while the courts and lawyers were sorting out the Walmart battle, Nicholas Loufrani was working on his next conquest, and it was bringing his Smiley into the digital world. He wanted more than just appearances on the growing number of computer and mobile screens across the world, he wanted to insert the Smiley into communication itself.

Is Smiley the first emoji? Not even close. People had been using what were then-called “emoticons” since the early 80s–and they can be traced back much farther than that.

Possibly the first emojis, circa 1938.

Although the primary set of yellow Smileys bear an undeniable relation to Ball’s original design, the invention of emoticons is commonly credited to Shigetaka Kurita of the Japanese telecom company NTT Docomo,

But Loufrani once again saw an opportunity to capitalize on the exploding digital media scene.

In 1999, The Smiley Company rolled out the first set of “portrait emoticons” with over 470 iterations, including wink Smiley, angry Smiley, animal Smileys, fruit Smileys, flag Smileys, Statue of Liberty Smiley.

Now there was truly a smiley for everything. You could call it a world of smileys.

In fact, that’s what he did. Loufrani launched a new brand called SmileyWorld to hold all of his new creations in the digital realm–and license them to mobile companies like Nokia and Samsung. In 2001, their slogan became “The birth of a new universal language.”

The big tech companies Apple and Microsoft came out with their own proprietary emoticons soon after. The Smiley was becoming part of everyday language, and the company benefitted tremendously, capitalizing on the trend by licensing them around the world and rolling out new partnerships with plush toys, games, food companies, and fashion retailers.

“When emojis started to pick up, we were seen as the originator, and it gave us a renewed credibility,” said Loufrani. “The smiley was cool again.”

New legal battles were most likely happening behind the scenes as the popularity and adoption of emojis spread. Or maybe Nicolas Loufrani and The Smiley Company were too busy counting their money. 🤑

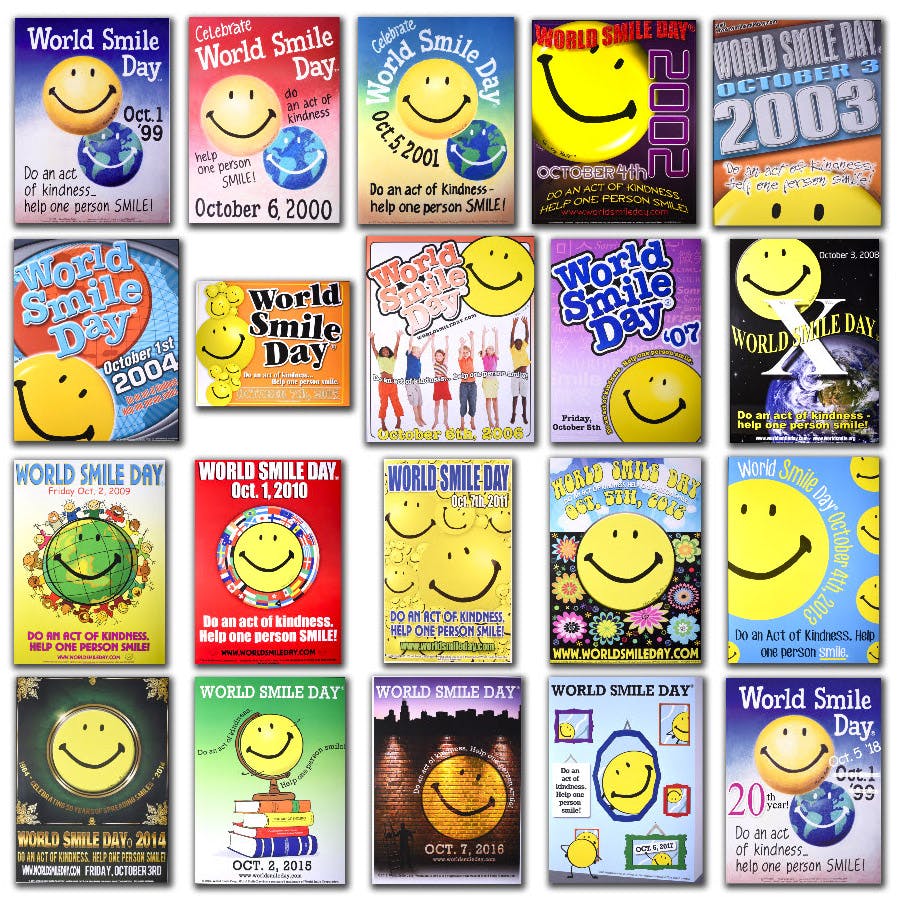

Smiley gets its day

Meanwhile, back in Worcester, New York, where we started this story, Harvey Ball wasn’t all smiles about how ubiquitous his creation had become. It wasn’t about the lost money or the lack of recognition; it was deeper than that.

“Smiley has become so commercialized that its original message of spreading goodwill and good cheer has all but disappeared. I needed to do something to change that.” –Harvey Ball, 1999

What Harvey did was the opposite of what Loufrani had done. He started a charity event called “World Smile Day,” to be held every year on the first Friday in October. The annual event would raise money for The Harvey Ball World Smile Foundation, a charitable trust that supports various children’s causes.

Its slogan is “Do an act of kindness–help one person smile!”

He also formed the World Smile Corporation to go after Smiley licensing opportunities. But he declined to receive any sort of compensation, deciding that all after-tax profits would be donated to charities. The Harvey Ball World Smile Foundation is now the vehicle that channels those after-tax profits to various charities.

If there’s a hero in this story, it’s Harvey Ball.

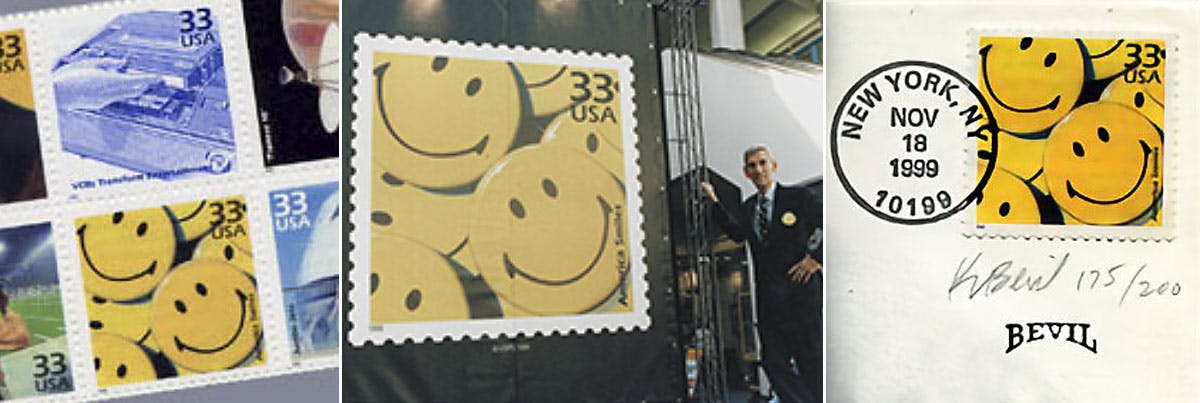

Smiley goes postal

In 1999, the Post Office conducted a poll to see what the public wanted to see on their soon-be-be-released stamps based on the ’70s, in five different categories, and our beloved Smiley won by a landslide in the “lifestyle” category, beating out competition like jogging, 70s fashion, and even disco!

Was it Loufrani’s Smiley Company that got the nod? Nope. It was the man considered to be the original creator–good ol’ Harvey Ball.

They unveiled the Smiley face commemorative stamp on the first-ever World Smilie Day, where they were the first to see the new stamp. No word on a disco dance after-party.

Smiley says goodbye

On April 12, 2001, Harvey Ball died at age 79 after a brief illness. One of his sons, Charles Ball, took over running the company and the charity. His organization, his annual event, and his extensive family continue his legacy to this day.

But it’s his simple creation, the Smiley, known around the world as the symbol of happiness and good cheer, that is his true legacy.

Smiley goes mainstream

In the subsequent 20+ years after the death of Harvey Ball, it’s almost impossible to overstate how omnipresent the humble Smiley has become in popular culture. Reinvented and redefined by generations of activists, artists, and creators, the Smiley continues to thrive and influence future generations.

Over the course of its trajectory from a marketing idea, to niche markets, to a counter-culture symbol, to being co-opted by bands and brands and appearing on products all around the world, even as its meaning and usage ebbed and flowed, the overall popularity of the Smiley never stopped growing, and its pervasive influence is literally everywhere.

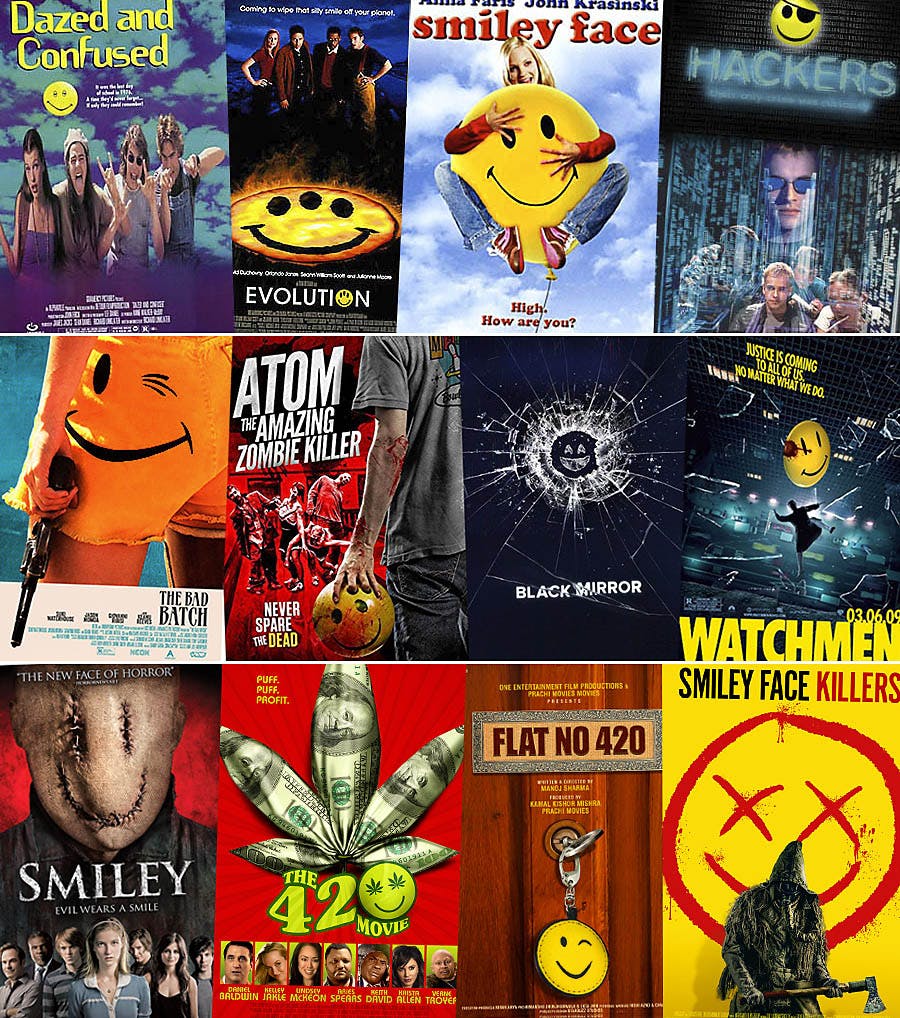

Smiley goes to the movies

Throughout the 2000s, the Smiley appeared in countless movies, as well as TV shows. Not only just appearing, but prominently displayed in promotional materials, or sometimes even being the premise itself.

From comedies to horror, the Smiley played a starring role, whether as its innocent feel-good origins or as its subverted, cynical alter-ego.

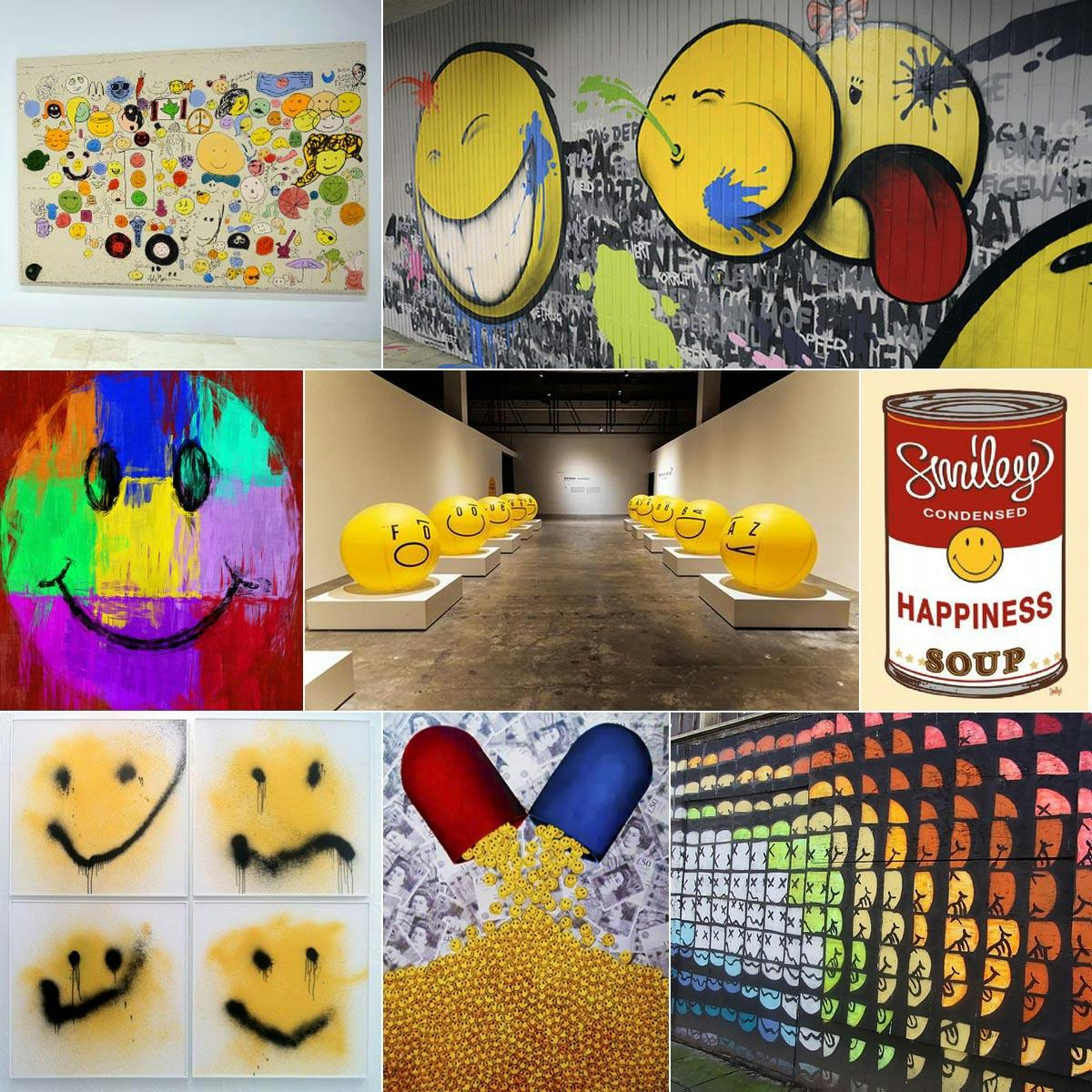

Smiley goes to the galleries

As a prominent cultural symbol, inevitably, the Smiley would make its way to the art world. Artists like the mysterious Banksy and pop art surrealists like Takashi Murakami used the symbol in various works, but in different ways.

Smiley gets the Banksy treatment in his street art.

Takashi Murakami made the Smiley a recurring part of his work.

Banksy superimposed the Smiley onto the figures of riot police and the grim reaper to subvert the meaning, whereas Murakami used it in its pure form as a signifier of unbridled joy.

Others deconstructed the symbol, questioned its meaning in the modern world, or elevated its simplicity. A design originally commissioned for 45 bucks is now fetches hundreds of thousands of dollars at auctions.

Smiley gets back in fashion

Don’t call it a comeback, because the Smiley never went away. But in the late 2010s, Smiley fashion culture came back around in a big way. Major fashion brands started incorporating the face, re-appropriating its original happy yellow positive vibes.

As Teen Vogue puts it, “With the resurgence of ’90s nostalgia, not unlike the recent tie-dye trend, it makes sense that the smiley face has come back in vogue.”

With influencers and celebrities wearing the iconic symbol, of course, the public followed suit. Justin Bieber even came with a fashion line that seems to be entirely based on the Smiley face.

Smiley turns 50

In 2022 the Smiley face turned 50 years old, and the Smiley company is celebrating the occasion by releasing the Collectors Edition featuring limited-edition apparel, accessories, and décor items from over 50 premier brands including Alice & Olivia, Michael Kors, Moschino, Raf Simons, and more, along with pop-up shops and other events.

The staying power of this symbol is undeniable. Whether in its original form of joyful optimism or its darker, more subversive alter-egos, the Smiley is here to stay. It could very well be the most popular graphic icon of all time.

“Never in the history of mankind has any single piece of art gotten such widespread favor, pleasure, enjoyment, and nothing has ever been so simply done and so easily understood in art.” – Harvey Ball

Make a Smiley T-shirt of your own

Now that you’re inspired by the rich and wild history of the Smiley face, what better time to design your own? Our clip art library has dozens of versions of the Smiley face (royalty free), or you can upload your own for a truly unique creation.

Just a few of the many smiley face graphics available in our clip art library.

When you’re ready to make your own cultural icon T-shirt, fire up our newly-redesigned Design Studio, and get creative! 😊

Imri Merritt

About the Author

A graduate of the Multimedia program at the University of the Arts in Philadelphia, Imri Merritt is an industry veteran with over 20 years of graphic design and color separations experience in the screen printing industry.